John Hickey from the Connecting the Culm team, describes a recent guided walk along the Culm.

We gathered on a fine September evening to hear about the heritage and environment of the Culm. The event, part of the Blackdown Hills Festival of Heritage 2025 organised by Blackdown Hills National Landscape, was led by Lucy Jefferson from the Connecting the Culm Project.

We started at the medieval Culmstock Bridge where Lucy explained the vital connections running through the valley at this ancient river crossing. The adjacent old railway line, which we followed downstream on our walk, was named ‘The Milk Line’ – for decades, this line delivered rich butter, cheese and milk from the factory at Hemyock, down through Uffculme to Tiverton junction, and onto London.

Our first stop down the line was to meet Richard Horrocks. Richard and other members from the local fishing club volunteer to monitor the water quality of the River Culm. This is done by kick sampling: collecting aquatic macro-invertebrates, the riverflies that live in amongst the gravels and aquatic plants of the river. Three times a year, in spring, summer and autumn, the volunteers undertake their sampling and then identify the riverflies that they catch. Riverflies are a key part of the river ecosystem, being food for a wide variety of fish and birds. Riverflies also happen to be very good indicators of the water quality of the river. Some, like midge larvae, are very tolerant of pollution, whilst others such as caddis flies, may flies and stone flies are very sensitive to pollution and require excellent water quality to be found in good numbers in the river. Richard showed the group the autumn sample that he collected. Unfortunately at the time, the diversity of insects and their abundance after the summer drought was fairly poor. A pristine river can obtain a maximum score of 24, on this occasion the score for the sample was only 8. In the headwaters of the Culm (just upstream of Hemyock) the River often scores very well, often up to 20 which is an extremely good score compared indeed to any river in the country. However, even here the autumn score was only 14, perhaps an indication of the pressure the river has been under from low flows. Overall it does seem that the river drops off in its water quality as it moves on downstream from Hemyock. Richard also took some chemical samples. The Phosphate level on this occasion was also relatively high, at 0.7 mg/l which is over seven times higher than it should be for a clean river. This is noticeable in the actual look of the river, where algae, fed by the phosphorus, is encouraged to grow quickly, smothering the gravels and plants on the river bed and reducing the quality of the river habitat. In conclusion, works do seem to be required to improve the quality in this section of the river.

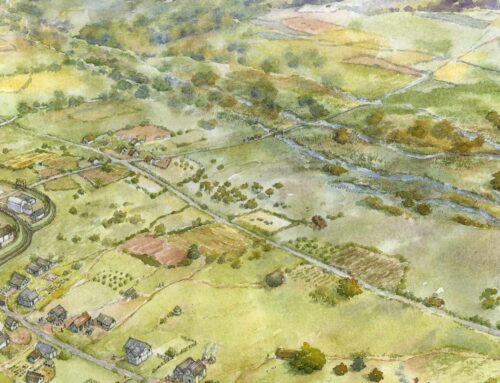

The Culm valley and its landscape with its rich tapestry of fields and hedges has been shaped by agriculture over hundreds of years. The floodplain is no exception and has been changed significantly by humans over many centuries. Thousands of years ago extensive wet woodland dominated the wide valley bottom; this is evidenced by organic deposits which have been revealed by the river eroding its bed and banks in recent times. These woody and dark rich organic material deposits are from a wet woodland that dominated the valley over 1000 years ago. Through this wet woodland flowed the river Culm, in a very different form to today, through multiple branching shallow channels. With all the tree roots this was far more resistant to erosion, very different from what you see today, with the dominant single channel significantly eroding its steep high banks quite obviously in several places along the route between Culmstock and Uffculme.

The removal of the floodplain woodland, and the intensification of farming across the valley slopes, allowed the more general erosion of the valley sides. The eroded material from the hillsides has been deposited in the valley bottom over many hundreds of years. This build up of deposited silts and sands makes up the rich alluvial floodplain that we see today. Five hundred years ago this rich land was highly prized and was managed very carefully, being kept warm and fertilised through the winter by extensive water meadow systems. Devon, in particular the Culm and Exe valleys, had as a great a number of catch and bed work water meadows as anywhere in the country. This was likely driven by the significant trade in wool textile products being made locally and exported across Europe from Exeter and Topsham.

Our final stop of discovery along the river was to meet some of the team from the Wildwoods Trust working hard to prevent the extinction of the rare White Clawed Crayfish in Devon. Their last stronghold in the river Culm is under significant threat; partly by the invasive, larger and more aggressive American signal crayfish, which were introduced and escaped from ponds stocked since the 1970’s; and partly by the loss and degradation of their river habitat. White-clawed crayfish require clean water and good physical habitat for cover, including from aquatic plants and tree roots found along stable riverbanks. By restoring the river and re-connecting it to its floodplain, good river bank habitat with good water quality can be achieved.

The invasive American crayfish have been steadily taking over the river Culm, so to save the local Devon population in the Culm, adults are being trapped and taken to a local hatchery for breeding and growing on of their young in protected pond site at Wildwood Devon. Works are also being undertaken to find other protected river sites that they may then in the future be reintroduced to ensure the survival of the Devon populations.

This concluded the walk and a beautiful evening. As the sun set the group enjoyed their stroll back to Culmstock.

Leave A Comment